Aerospace machining is full of paradoxes. You cut high-value parts from expensive alloys, then remove 80–95% of the material. Your final geometry is often thin, light, and flexible, yet it must hold tight tolerances across large spans. The machine may be a five-axis masterpiece and the toolpath may be perfect, but none of that matters if the part moves under clamping or springs when you release it.

Thin-wall distortion is one of the most common causes of aero scrap and rework. It’s also one of the most misunderstood. Many shops react with either excessive clamping (“hold it harder so it won’t move”) or timid clamping (“hold it lightly so it won’t distort”). Both approaches fail because distortion is not only about how much force you apply; it’s about where, how evenly, and how repeatably you apply it.

This blog walks through a practical strategy for thin-wall aerospace workholding that supports accuracy without drama.

Why thin-wall parts distort

A thin-wall part is essentially a spring. When you clamp it, the wall deflects. When you machine it, the cutting load deflects it again. When you unclamp, residual stress and elastic recovery shift it into its free state.

The distortion sources are usually:

- clamping force concentration at a few high-pressure points

- uneven seating that bends the part into the fixture

- residual stress release as material is removed

- gravity vector changes in five-axis cutting

If your fixture and process don’t predict and control these influences, the part will not come out stable.

Principle 1: Separate location from clamping

Aerospace parts need to be located precisely but clamped gently. That means your fixture should use hard, repeatable locators to set datum and distributed clamping to hold without bending.

This is much easier when your fixture baseline to the machine is highly repeatable. If you can remove and re-install a thin-wall fixture without re-indicating, you gain the freedom to inspect between ops and to re-clamp with confidence.

Many aerospace cells standardize their machine-fixture datum transfer using repeatable zero-point families such as 3r systems, so thin-wall setups can move through rough-inspect-finish loops without losing coordinate truth.

Principle 2: Clamp symmetrically whenever possible

Where geometry permits, symmetric clamping is your friend. It balances force paths and reduces the tendency of the part to “walk” into a stop or twist.

Self-centering clamping doesn’t solve every aero fixture problem, but it shines in prismatic brackets, housings, and structural subcomponents. When jaws travel evenly and pull toward the midline, seating becomes more repeatable and the likelihood of bending due to bias drops.

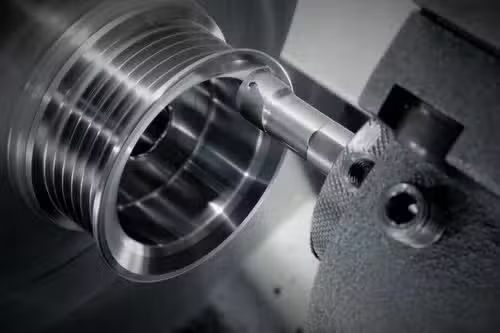

That’s why many aero shops keep self-centering systems in their general tooling kit for suitable geometries; a typical example is CNC Self Centering Vise, used to reduce uneven clamping and speed repeatable seating on thin-section work.

Principle 3: Distribute contact, reduce pressure

Clamping pressure equals force divided by area. Thin walls hate pressure spikes. So you want large contact areas, soft pads, or custom clamping shoes that spread the load.

Even if total force is moderate, a small jaw corner can create a pressure canyon that dents or bends the wall. Increasing contact area flattens the force curve.

Principle 4: Machine in a distortion-aware sequence

Workholding is only half the fight. Your machining order changes how stress releases.

Common best practices:

- rough in a way that keeps ribs balanced until late

- avoid removing all support material on one side early

- alternate cuts to keep stiffness symmetric

- leave finishing stock for a post-inspection clamp

When you remove stiffness too early, even a perfect fixture can’t stop distortion.

Principle 5: Expect movement and measure it

Aerospace workholding success depends on acknowledging that movement will happen. The question is whether it happens in a predictable loop you can control.

A stable aero workflow looks like this:

- rough with conservative clamps

- remove and inspect

- re-install on repeatable datum

- finish with light, distributed clamping

Because the datum transfer is stable, your inspection data becomes actionable rather than frustrating.

Fixturing tactics that work in practice

Here are tactics that repeatedly succeed in thin-wall production:

- hard locators + soft clamps

- vacuum assist for broad surfaces

- step clamps on stiff ribs, not thin skins

- compliant pads that self-seat

- torque-scribes or digital torque checks

The recurring theme: make location certain and clamping gentle.

Avoid these common aero mistakes

- clamping on thin skins when ribs or bosses are available

- re-indicating after every inspection (kills consistency and speed)

- over-relying on friction instead of geometric location

- ignoring thermal drift on long cycles

- finishing before the part has stabilized after roughing

Closing thought

Thin-wall aerospace machining is not about eliminating movement; it’s about controlling it. If you separate location from clamping, clamp symmetrically where possible, distribute contact, and tie the whole loop to a repeatable datum baseline, thin-wall parts stop being unpredictable springs and start behaving like manageable structures. Accuracy becomes repeatable, not heroic.